MAKER Tutorial for GMOD Online Training 2014

Contents

- 1 About MAKER

- 2 Introduction to Genome Annotation

- 3 MAKER Overview

- 4 MAKER-P

- 5 Installation

- 6 Getting Started with MAKER

- 7 Details of What is Going on Inside of MAKER

- 8 MAKER's Output

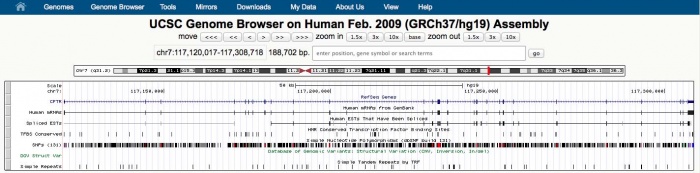

- 9 Viewing MAKER Annotations

- 10 Advanced MAKER Configuration, Re-annotation Options, and Improving Annotation Quality

About MAKER

MAKER is an easy-to-use genome annotation pipeline designed for small research groups with little bioinformatics experience. However, MAKER is also designed to be scalable and is thus appropriate for projects of any size including use by large sequence centers. MAKER can be used for de novo annotation of newly sequenced genomes, for updating existing annotations to reflect new evidence, or just to combine annotations, evidence, and quality control statistics for use with other GMOD programs like GBrowse, JBrowse, Chado, and Apollo.

MAKER has been used in many genome annotation projects (these are just a few):

- Schmidtea mediterranea - planaria (A Alvarado, Stowers Institute) PubMed

- Pythium ultimum oomycete (R Buell, Michigan State Univ.) PubMed

- Pinus taeda - Loblolly pine (A Stambolia-Kovach, Univ. California Davis) PubMed

- Atta cephalotes - leaf-cutter ant (C Currie, Univ. Wisconsin, Madison) PubMed

- Linepithema humile - Argentine ant (CD Smith, San Francisco State Univ.) PubMed

- Pogonomyrmex barbatus - red harvester Ant (J Gadau, Arizona State Univ.) PubMed

- Conus bullatus - cone snail (B Olivera Univ. Utah) PubMed

- Petromyzon marinus - Sea lamprey (W Li, Michigan State) PubMed

- Fusarium circinatum - pine pitch canker (B Wingfield, Univ. Pretoria) - Manuscript in preparation

- Cardiocondyla obscurior - tramp ant (J Gadau, Arizona State Univ.) - Manuscript in preparation

- Columba livia - pigeon (M Shapiro, Univ. Utah) - Manuscript in preparation

- Megachile routundata alfalfa leafcutter bee () - Manuscript in preparation

- Latimeria menadoensis - african coelacanth () - PubMed

- Nannochloropsis - micro algae (SH Shiu, Michigan State Univ.) PubMed

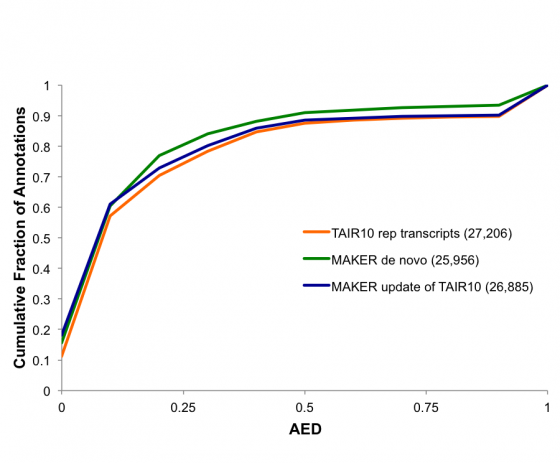

- Arabidopsis thale cress re-annotation (E Huala, TAIR) - Manuscript in preparation

- Cronartium quercuum - rust fungus (JM Davis, Univ. Florida) - Annotation in progress

- Ophiophagus hannah - King cobra (T. Castoe, Univ. Colorado) - Annotation in progress

- Python molurus - Burmese python (T. Castoe, Univ. Colorado) - Annotation in progress

- Lactuca sativa - Lettuce (RW Michelmore) - Annotation in progress

- parasitic nematode genomes (M Mitreva, Washington Univ)

- Diabrotica virgifera - corn rootworm beetle (H Robertson, Univ. Illinois)

- Oryza sativa - rice re-annotation (R Buell, MSU)

- Zea mays - maize re-annotation (C Lawrence, MaizeGDP)

- Cephus cinctus - wheat stem sawfly (H Robertson, Univ. Illinois)

- Rhagoletis pomonella - apple maggot fly (H Robertson, Univ. Illinois)

There are many more projects that use MAKER around the world.

Introduction to Genome Annotation

What Are Annotations?

Annotations are descriptions of different features of the genome, and they can be structural or functional in nature.

Examples:

- Structural Annotations: exons, introns, UTRs, splice forms (Sequence Onotology)

- Functional Annotations: process a gene is involved in (metabolism), molecular function (hydrolase), location of expression (expressed in the mitochondria), etc. (Gene Ontology)

It is especially important that all genome annotations include an evidence trail that describes in detail the evidence that was used to both suggest and support each annotation. This assists in curation, quality control and management of genome annotations.

Examples of evidence supporting a structural annotation:

- Ab initio gene predictions

- Transcribed RNA (mRNA-Seq/ESTs/cDNA/transcript)

- Proteins

Importance of Genome Annotations

Why should the average biologist care about genome annotations?

Genome sequence itself is not very useful. The first question that occurs to most of us when a genome is sequenced is, "where are the genes?" To identify the genes we need to annotate the genome. And while most researchers probably don't give annotations a lot of thought, they use them everyday.

Examples of Annotation Databases:

Every time we use techniques such as RNAi, PCR, gene expression arrays, targeted gene knockout, or ChIP we are basing our experiments on the information derived from a digitally stored genome annotation. If an annotation is correct, then these experiments should succeed; however, if an annotation is incorrect then the experiments that are based on that annotation are bound to fail. Which brings up a major point:

- Incorrect and incomplete genome annotations poison every experiment that uses them.

Quality control and evidence management are therefore essential components to the annotation process.

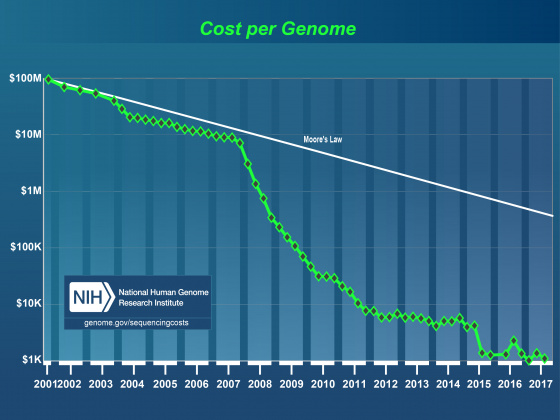

Effect of NextGen Sequencing on the Annotation Process

It’s generally accepted that within the next few years it will be possible to sequence even human sized genomes for as little as $1,000. As costs have drop, read lengths have increased, and assembly and alignment algorithms have matured, the genome project paradigm is shifting. Even small research groups are turning their focus from the individual reference genome to the population. This shift in focus has already lead to great insights into the genomic effects of domestication and is very promising in helping us understand multiple host-pathogen relationships. Importantly, these population-based studies still require a well-annotated reference genome. Unfortunately, advances in annotation technology have not kept pace with genome sequencing, and annotation is rapidly becoming a major bottleneck affecting modern genomics research.

For example:

- As of May 2014, 6,883 eukaryote and 16,745 prokaryote genome projects were underway.

- If we assume 10,000 genes per genome, that’s over 230,000,000 new annotations (with this many new annotations, quality control and maintenance is a major issue).

- While there are organizations dedicated to producing and distributing genome annotations (i.e ENSEMBL, JGI, Broad), the shear volume of newly sequenced genomes exceeds both their capacity and stated purview.

- Small research groups are affected disproportionately by the difficulties related to genome annotation, primarily because they often lack bioinformatics resources and must confront the difficulties associated with genome annotation on their own.

MAKER is an easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed to help smaller research groups convert the coming tsunami of genomic data provided by next generation sequencing technologies into a usable resource.

MAKER Overview

The easy-to-use annotation pipeline.

The easy-to-use annotation pipeline.

| User Requirements: | Can be run by small groups (single individual) with a little linux experience |

|---|---|

| System Requirements: | Can run on desktop computers running Linux or Mac OS X (but also scales to large clusters) |

| Program Output: | Output is compatible with popular GMOD annotation tools like Apollo, GBrowse JBrowse |

| Availability: | Free, open-source application (academic use) |

What does MAKER do?

- Identifies and masks out repeat elements

- Aligns ESTs to the genome

- Aligns proteins to the genome

- Produces ab initio gene predictions

- Synthesizes these data into final annotations

- Produces evidence-based quality values for downstream annotation management

What sets MAKER apart from other tools (ab initio gene predictors etc.)?

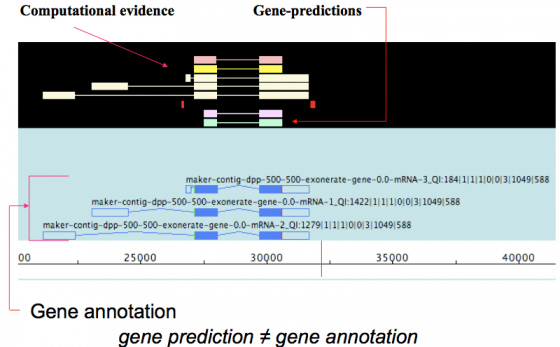

MAKER is an annotation pipeline, not a gene predictor. MAKER does not predict genes, rather MAKER leverages existing software tools (some of which are gene predictors) and integrates their output to produce what MAKER finds to be the best possible gene model for a given location based on evidence alignments.

gene prediction ≠ gene annotation

- gene predictions are partial gene models.

- gene annotations are gene models but should include a documented evidence trail supporting the model in addition to quality control metrics.

This may seem like a matter of semantics since the output for both ab initio gene predictors and the MAKER pipeline are conceptually the same - a collection of gene models. However there are significant differences that are discussed below.

Emerging vs. Classic Model Genomes

Not all genomes are created equal - each comes with its own set of issues that are not necessarily found in classic model organism genomes. These include difficulties associated with repeat identification, gene finder training, and other complex analyses. Emerging model organisms are often studied by small research communities which may lack the infrastructure and bioinformatics expertise necessary to 'roll-ther-own' annotation solution.

| 'Old School' Model Organism Annotation | 'New Cool' Emerging Organism Annotation |

|---|---|

|

Well developed experimental systems |

The genome will be a central resource for experimental design |

|

Much prior knowledge about genome/transcriptome/proteome |

Limited prior knowledge about genome |

| Large community | Small communities |

| $$$ | $ |

| Examples: D. melanogaster, C. elegans, human | Examples: oomycetes, flat worms, cone snail |

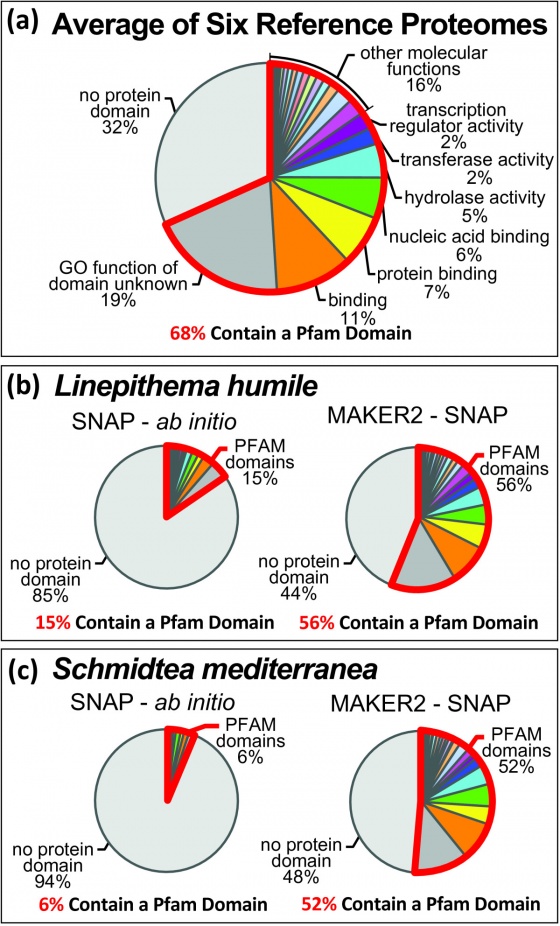

Comparison of Algorithm Performance on Model vs. Emerging Genomes

If you have looked at a comparison of gene predictor performance on classic model organisms such as C. elegans you might conclude that ab initio gene predictors match or even outperform state of the art annotation pipelines, and the truth is that, with enough training data, they do very well. It is important to keep in mind, however, that ab initio gene predictors have been specifically optimized to perform well on model organisms such as Drosophila and C. elegans, organisms for which we have large amount of pre-existing data to both train and tweak the prediction parameters.

What about emerging model organisms for which little data is available? Gene prediction in classic model organisms is relatively simple because there are already a large number of experimentally determined and verified gene models, but with emerging model organisms, we are lucky to have a handful of gene models to train with. As a result ab initio gene predictors generally perform very poorly on emerging genomes.

By using ab inito gene predictors within the MAKER pipeline you get several key benefits:

- MAKER provides gene models together with an evidence trail - useful for manual curation and quality control.

- MAKER provides a framework within which you can train and retrain gene predictors for improved performance.

- MAKER's output (including supporting evidence) can easily be loaded into a GMOD compatible database for annotation distribution.

- MAKER's annotations can be easily updated with new evidence by passing existing annotation sets back though MAKER.

MAKER-P

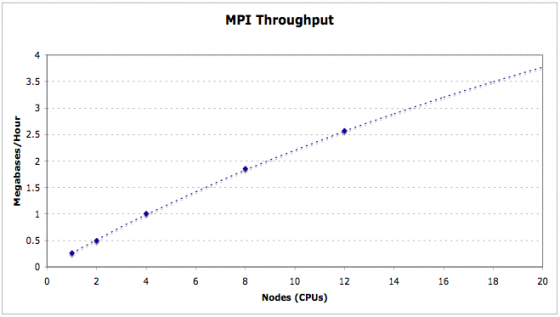

MAKER-P was recently published in Plant Physiology. The original purpose of the MAKER-P project was to produce a genome annotation pipeline for annotating plants. Plants are notoriously hard annotation targets. Plant genomes commonly large and highly repetitive; they contain a large number of pseudogenes, and novel protein coding and non-coding genes. To address these challenges we optimized MAKER's performance on large computing clusters such at TACC, developed tutorials for custom repeat library generation, optimized current pseudogene identification pipelines for use with standard MAKER outputs, and incorporated non-coding RNA annotation capabilities into MAKER. This ultimately resulted in a version of MAKER could annotate the most challenging of plant genomes and showed no performance loss on animal genomes. Originally the '-P' in MAKER-P stood for 'Plant', in reality it can be thought of as MAKER-Plus, MAKER-parallelized , or MAKER-Plant depending on your needs.

Performance on large computing clusters

MAKER is fully MPI compliant and plays well with Open MPI and MPICH2. MAKER is installed and available for iPlant users on the lonestar cluster at the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC). Here you can see the entire maize v2 genome (~2 Gb) can be annotated in just over 2 hours using as few as 500 cpus. MAKER-P was also used to annotate the largest genome ever sequenced (loblolly pine, >20 Gb) in less than 15 hours runtime on 8,640 cpus (37 hours total when including queue wait time).

Tutorials for custom repeat library generation

Many of the interesting genomes we are currently sequencing as a genomics community are not being sequenced because of their similarities to previously sequenced genomes but because of their dis-similarities. These phylogenetically distant organisms not only present unique protein coding genes but also a multitude of previously unseen repetitive elements. For the best annotation results a species specific repeat library should be used in masking the genome prior to annotation. We have provided basic Repeat Library Construction--Basic and advanced Repeat Library Construction--Advanced tutorials for creating these libraries. A pipeline that automates this process is currently in development.

Pseudogene identification pipeline

The current pseudogene pipeline utilized by MAKER defines pseudogenes as intergenic sequences with significant resemblance to annotated proteins in that genome. instructions for running this pipeline can be found here Protocol:Pseudogene. This protocol can be adapted to find pseudogenes without similarity to protein coding genes in the organism but similar to genes in closely related species by modifying the input sequences to the pipeline.

Non-coding RNA annotation

tRNAscan-SE and snoscan are now part of the MAKER framework. Annotating tRNAs is now as simple as setting a single option in the maker_opts.ctl file. tRNAscan-SE runs quickly and accurately. Annotating snoRNAs requires the user to pass a file containing annotated rRNAs for the organism of interest in fasta format to MAKER through the maker_opts.ctl file. Currently all snoscan annotations are being promoted to the final annotation set. To increase specificity and overall accuracy, a filter based on AED will soon be implemented. miR-PREFeR was developed for miRNA annotation as part of the MAKER-P tool kit and has yet to be incorporated into the MAKER framework. At this time miR-PREFeR is run as a stand-alone tool and the output can be passed to MAKER in the maker_opts.ctl as 'other_gff=' for inclusion in the final gff3 file.

Installation

Prerequisites

Perl Modules

- BioPerl

- DBI

- File::Which

- Perl::Unsafe::Signals

- Bit::Vector

- Inline

- Inline::C

- forks

- forks::shared

- IO::All(Optional, for accessory scripts)

- IO::Prompt(Optional, for accessory scripts)

External Programs

- Perl 5.8.8 or Higher

- SNAP version 2009-02-03 or higher

- RepeatMasker 3.1.6 or higher

- Exonerate 1.4 or higher

- NCBI BLAST 2.2.X or higher

Optional Components:

- Augustus 2.0 or higher

- GeneMark-ES 2.3a or higher

- FGENESH 2.6 or higher

Required for optional MPI support:

The MAKER Package

MAKER can be downloaded from:

- http://www.yandell-lab.org/ - but it should already be on the image

MAKER is already installed on the Amazon Machine Image that we will be using today, so let's start an instance of that AMI. Navigate your browser to:

The AWS EC2 Management Console

Search for the AMI named MAKER_2.31.5_Tutorial

Launch and instance of that AMI with the following parameters:

- Instance Type: Small (m1.small)

- Use a security group with:

- Allow SSH (port 22)

- Allow HTTP (port 80)

When the machine is running connect to it with SSH (puTTY):

ssh -i ~/.ec2/my_private_key.pem ec2-user@ec2-##-##-##-##.compute-1.amazonaws.com

Ensure you change the user name from root to ec2-user

Now that we're on our MAKER annotation server let's look at our MAKER installation:

cd /usr/local/maker ls -1

Note: That is a dash one, not a dash L, on the ls command.

You should now see the following:

GMOD INSTALL LICENSE MWAS README bin data lib perl src

There are two files in particular that you would want to look at when installing MAKER - INSTALL and README. INSTALL gives a brief overview of MAKER and prerequisite installation. Let's take a look at this.

less INSTALL

You really only need to follow the instructions for the EASY INSTALL, unless you have a problem/error during installation. Then you can follow the detailed install instructions in the file.

***Installation Documentation***

How to Install Standard MAKER

!!IMPORTANT NOTE FOR MAC OS X USERS!!

You will need to install developer tools (i.e. Xcode) from the App Store or

your installation disk. Also install fink (http://www.finkproject.org/) and

then install glib2-dev via fink (i.e. 'fink install glib2-dev').

**EASY INSTALL

1. Go to the .../maker/src/ directory and run 'perl Build.PL' to configure.

2. Accept default configuration options by just pressing enter. See MPI INSTALL

in next section if you decide to configure for MPI.

3. type './Build install' to complete the installation.

4. If anything fails, either use the ./Build file commands to retry the failed

section (i.e. './Build installdeps' and './Build installexes') or follow the

detailed install instructions in the next section to manually install missing

modules or programs. Use ./Build status to see available commands.

./Build status #Shows a status menu

./Build installdeps #installs missing PERL dependencies

./Build installexes #installs missing external programs

./Build install #installs MAKER

Note: You do not need to be root. Just say 'yes' to 'local install' when

running './Build installdeps' and dependencies will be installed under

.../maker/perl/lib, also missing external tools will be installed under

.../maker/exe when running './Build installexes'.

Note: For failed auto-download of external tools, when using the command

'./Build installexes', the .../maker/src/locations file is used to identify

download URLs. You can edit this file to point to any alternate locations.

Getting Started with MAKER

Note

Before we begin with example data I want everyone to note that there are finished examples are located in example data folder, so if you fall behind you can always find MAKER control files datasets and final results in there.

First let's test our MAKER executable and look at the usage statement:

maker -h

MAKER version 2.31.5

Usage:

maker [options] <maker_opts> <maker_bopts> <maker_exe>

Description:

MAKER is a program that produces gene annotations in GFF3 format using

evidence such as EST alignments and protein homology. MAKER can be used to

produce gene annotations for new genomes as well as update annotations

from existing genome databases.

The three input arguments are control files that specify how MAKER should

behave. All options for MAKER should be set in the control files, but a

few can also be set on the command line. Command line options provide a

convenient machanism to override commonly altered control file values.

MAKER will automatically search for the control files in the current

working directory if they are not specified on the command line.

Input files listed in the control options files must be in fasta format

unless otherwise specified. Please see MAKER documentation to learn more

about control file configuration. MAKER will automatically try and

locate the user control files in the current working directory if these

arguments are not supplied when initializing MAKER.

It is important to note that MAKER does not try and recalculated data that

it has already calculated. For example, if you run an analysis twice on

the same dataset you will notice that MAKER does not rerun any of the

BLAST analyses, but instead uses the blast analyses stored from the

previous run. To force MAKER to rerun all analyses, use the -f flag.

MAKER also supports parallelization via MPI on computer clusters. Just

launch MAKER via mpiexec (i.e. mpiexec -n 40 maker). MPI support must be

configured during the MAKER installation process for this to work though

Options:

-genome|g <file> Overrides the genome file path in the control files

-RM_off|R Turns all repeat masking options off.

-datastore/ Forcably turn on/off MAKER's two deep directory

nodatastore structure for output. Always on by default.

-old_struct Use the old directory styles (MAKER 2.26 and lower)

-base <string> Set the base name MAKER uses to save output files.

MAKER uses the input genome file name by default.

-tries|t <integer> Run contigs up to the specified number of tries.

-cpus|c <integer> Tells how many cpus to use for BLAST analysis.

Note: this is for BLAST and not for MPI!

-force|f Forces MAKER to delete old files before running again.

This will require all blast analyses to be rerun.

-again|a recaculate all annotations and output files even if no

settings have changed. Does not delete old analyses.

-quiet|q Regular quiet. Only a handlful of status messages.

-qq Even more quiet. There are no status messages.

-dsindex Quickly generate datastore index file. Note that this

will not check if run settings have changed on contigs

-nolock Turn off file locks. May be usful on some file systems,

but can cause race conditions if running in parallel.

-TMP Specify temporary directory to use.

-CTL Generate empty control files in the current directory.

-OPTS Generates just the maker_opts.ctl file.

-BOPTS Generates just the maker_bopts.ctl file.

-EXE Generates just the maker_exe.ctl file.

-MWAS <option> Easy way to control mwas_server for web-based GUI

options: STOP

START

RESTART

-version Prints the MAKER version.

-help|? Prints this usage statement.

Next let's quickly take a look at our data folders

cd ~/maker_tutorial ls -1

You should see several example folders.

example1_basic example2_abinitio example3_passthrough example4_legacy example5_features example6_postannotation

Let's look inside example1

ls -1 example1_basic dpp_contig.fasta dpp_contig.maker.output dpp_est.fasta dpp_protein.fasta finished.tgz opts.txt

You will see a directory called dpp_contig.maker.output, a file called opts.txt, and another file called finished.tgz. The directory contains much of the final results for the example (think of it as the pre-baked food in a cooking show), the finished.tgz file is just a backup of that directory, and the opts.txt file is a backup copy of the MAKER control file that we will be generating (more detail in a minute). Each of the other examples will contain a similar results directory and control file so if you fall behind or are impatient, then you can easily jump forward to the results.

Now let's get started!

Running MAKER with example data

MAKER comes with some example input files to test the installation and to familiarize the user with how to run MAKER. The example files are found in the .../maker/data directory.

ls -1 /usr/local/maker/data/ dpp_contig.fasta dpp_est.fasta dpp_protein.fasta hsap_contig.fasta hsap_est.fasta hsap_protein.fasta te_proteins.fasta

The example files are in FASTA format. MAKER requires FASTA format for its input files. Let's take a look at one of theses files to see what the format looks like.

less /usr/local/maker/data/dpp_protein.fasta >dpp-CDS-5 MRAWLLLLAVLATFQTIVRVASTEDISQRFIAAIAPVAAHIPLASASGSGSGRSGSRSVG ASTSTALAKAFNPFSEPASFSDSDKSHRSKTNKKPSKSDANRQFNEVHKPRTDQLENSKN KSKQLVNKPNHNKMAVKEQRSHHKKSHHHRSHQPKQASASTESHQSSSIESIFVEEPTLV LDREVASINVPANAKAIIAEQGPSTYSKEALIKDKLKPDPSTLVEIEKSLLSLFNMKRPP KIDRSKIIIPEPMKKLYAEIMGHELDSVNIPKPGLLTKSANTVRSFTHKDSKIDDRFPHH HRFRLHFDVKSIPADEKLKAAELQLTRDALSQQVVASRSSANRTRYQVLVYDITRVGVRG QREPSYLLLDTKTVRLNSTDTVSLDVQPAVDRWLASPQRNYGLLVEVRTVRSLKPAPHHH VRLRRSADEAHERWQHKQPLLFTYTDDGRHKARSIRDVSGGEGGGKGGRNKRQPRRPTRR KNHDDTCRRHSLYVDFSDVGWDDWIVAPLGYDAYYCHGKCPFPLADHFNSTNHAVVQTLV NNMNPGKVPKACCVPTQLDSVAMLYLNDQSTVVLKNYQEMTVVGCGCR

FASTA format is fairly simple. It contains a definition line starting with '>' that contains a name for a sequence followed by the actual nucleotide or amino acid sequence on subsequent lines. The file we are looking at contains protein sequences, so the sequence uses the single letter code for amino acids.

A minimal input file set for MAKER would generally consist of a FASTA file for the genomic sequence, a FASTA file of RNA (ESTs/cDNA/mRNA transcripts) from the organism, and a FASTA file of protein sequences from the same or related organisms (or a general protein database).

I've already copied these data files into the ~/maker/tutorial/example1_basic directory for you, but if you're following this tutorial outside of the course you can run directly inside the data directory to follow the first example or copy the files into a directory of your choice:

Now let's move to the first example.

cd ~/maker_tutorial/example1_basic

AS you can see it contains the same files as the data/ directory that comes with MAKER.

ls -1 dpp_contig.fasta dpp_contig.maker.output dpp_est.fasta dpp_protein.fasta finished.tgz opts.txt

Next we need to tell MAKER all the details about how we want the annotation process to proceed. Because there can be many variables and options involved in annotation, command line options would be too numerous and cumbersome. Instead MAKER uses a set of configuration files which guide each run. You can create a set of generic configuration files in the current working directory by typing the following.

maker -CTL

This creates three files (type ls -1 to see).

- maker_exe.ctl - contains the path information for the underlying executables.

- maker_bopt.ctl - contains filtering statistics for BLAST and Exonerate

- maker_opt.ctl - contains all other information for MAKER, including the location of the input genome file.

Control files are run-specific and a separate set of control files will need to be generated for each genome annotated with MAKER. MAKER will look for control files in the current working directory, so it is recommended that MAKER be run in a separate directory containing unique control files for each genome.

Let's take a look at the maker_exe.ctl file (here we use nano but you can use any text editor you want).

nano maker_exe.ctl

You will see the names of a number of MAKER supported executables as well as the path to their location. If you followed the installation instructions correctly, including the instructions for installing prerequisite programs, all executable paths should show up automatically for you. However if the location to any of the executables is not set in your PATH environment variable, as per installation instructions, you will have to add these manually to the maker_exe.ctl file every time you run MAKER.

Lines in the MAKER control files have the format key=value with no spaces before or after the equals sign(=). If the value is a file name, you can use relative paths and environment variables, i.e. snap=$HOME/snap. Note that for all control files the comments written to help users begin with a pound sign(#). In addition, options before the equals sign(=) can not be changed, nor should there be a space before or after the equals sign.

Now let's take a look at the maker_bopts.ctl file.

nano maker_bopts.ctl

In this file you will find values you can edit for downstream filtering of BLAST and Exonerate alignments. At the very top of the file you will see that I have the option to tell MAKER whether I prefer to use WU-BLAST or NCBI-BLAST. We want to set this to NCBI-BLAST, since that is what is installed. We can just leave the remaining values as the default.

blast_type=ncbi+

Now let's take a look at the maker_opts.ctl file.

nano maker_opts.ctl

This is the primary configuration file for MAKER specific options. Here we need to set the location of the genome, EST, and protein input files we will be using. These come from the supplied example files. If you are following this in class you can replace the maker_opts.ctl file with the opts.txt which is has options pre-filled for you. There are a lot of options in this file, and we'll discuss many of them in more detail later on in other examples. Below are the options we adjust with a text editor:

genome=dpp_contig.fasta

est=dpp_transcripts.fasta

protein=dpp_proteins.fasta

est2genome=1

or

cp opts.txt maker_opts.ctl

Note: You should not put spaces on either side of the = on the above control file lines.

Now let's run MAKER.

maker

You should now see a large amount of status information flowing past your screen. If you don't want to see this you can run MAKER with the -q option for "quiet" on future runs.

Details of What is Going on Inside of MAKER

Repeat Masking

The first step in the MAKER pipeline is repeat masking. Why do we need to do this? Repetitive elements can make up a significant portion of the genome. These repeats fall into to basic classes:

- Low-complexity (simple) repeats: These consist of stretches (sometimes very long) of tandemly repeated sequences with little information content. Examples of low-complexity sequence are mononucleotide runs (AAAAAAA, GGGGGG) and the various types of satellite DNA.

- Interspersed (complex) repeats - Sections of sequence that have the ability to change thier location within the genome. These transposons and retrotransposons contain real coding genes (reverse transcriptase, Gag, Pol) and have the ability to transpose (and often duplicate) surrounding sequence with them.

The low information content of the low complexity repeats sequence can produce sequence alignments with high statistical significance to low-complexity protein regions creating a false homology (think evidence for genes) throughout the genome.

Because these complex repeats contain real protein coding genes they play havoc with ab initio gene predictors. For example, a transposable element that occurs within the intron of one of the organism's own protein encoding genes might cause a gene predictor to include extra exons as part of this gene. Thus, sequence which really only belongs to a transposable element is included in your final gene annotation set.

Analysis of the repeat structure of a new genome is an important goal, but the presence of those repeats both simple and complex makes it nearly impossible to generate a useful annotation set of the organisms own genes. For this reason it is critical to identify and mask these repetitive regions of the genome.

MAKER identifies repeats in two steps.

- First MAKER runs a program called RepeatMasker is used to identify both all classes of repeats that match entries in the RepBase repeat library. You can even create your own species specific repeat library and RepeatMasker will use it in addition to its own libraries to mask repeats. Species specific repeat libraries can improve the annotation tremendously instructions for creating aa repeat library for your favorite organism can be found here Repeat Library Construction--Basic and here Repeat Library Construction--Advanced.

- Next MAKER uses RepeatRunner to identify transposable elements and viral proteins using the RepeatRunner protein database. Because RepeatRunner uses protein sequence libraries and protein sequence diverges at a slower rate than nucleotide sequence, this step picks up many problematic regions of divergent repeats that are missed by RepeatMasker (which searches in nucleotide space).

Regions identified during repeat analysis are masked out in two different ways:

- Complex repeats are hard-masked - the repeat sequence is replaced with the letter N. This essentially removes this sequence from any further consideration at any later point of the annotation process.

- Simple repeats are soft-masked - sequences are transformed to lower case. This prevents alignment programs such as Blast from seeding any new alignments in the soft-masked region, however alignments that begin in a nearby (non-masked) region of the genome can extend into the soft-masked region. This is important because low-complexity regions are found within many real genes, they just don't make up the majority of the gene.

Masking sequence from the annotation pipeline (especially hard masking) may seem like it might cause us to lose real protein coding genes that are important for the organism's biology. It is true that repeat derived genes can be co-opted and expressed by the organism and repeat masking will affect our ability to annotate these genes. However, these genes are rare and the number of gene models and sequence alignments improved by the repeat masking step far outweighs the few gene models that may be negatively affected. You do have the option to run ab initio gene predictors on both the masked and unmasked sequence if repeat masking worries you though. You do this by setting unmask:1 in the maker_opt.ctl configuration file.

Ab Initio Gene Prediction

Following repeat masking, MAKER runs ab initio gene predictors specified by the user to produce preliminary gene models. Ab initio gene predictors produce gene predictions based on underlying mathematical models describing patterns of intron/exon structure and consensus start signals. Because the patterns of gene structure are going to differ from organism to organism, you must train gene predictors before you can use them. I will discuss how to do this later on.

MAKER currently supports:

- SNAP (Works good, easy to train, not as good as others especially on longer intron genomes).

- Augustus (Works great, hard to train, but getting better)

- GeneMark (Self training, no hints, buggy, not good for fragmented genomes or long introns).

- FGENESH (Works great, costs money even for training)

You must specify in the maker_opts.ctl file the training parameters file you want to use use when running each of these algorithms.

RNA and Protein Evidence Alignment

A simple way to indicate if a sequence region is likely associated with a gene is to identify (A) if the region is actively being transcribed or (B) if the region has homology to a known protein. This can be done by aligning Expressed Sequence Tags (ESTs) and proteins to the genome using alignment algorithms.

- ESTs are sequences derived from a cDNA library. In recent years ESTs have been largely replaced by mRNA-seq data, which have decreases costs but have may of same challenges as traditional EST libraries. Because of the difficulties associated with working with mRNA and depending on how the cDNA library was prepared, EST databases and mRNA-seq assemblies usually represent bits and pieces of transcribed RNA with only a few full length transcripts. MAKER aligns these sequences to the genome using BLASTN. If ESTs/mrNA-seq from the organism being annotated are unavailable or sparse, you can use ESTs/mRNA-seq from a closely related organism. However, RNA from closely related organisms are unlikely to align using BLASTN since nucleotide sequences can diverge quite rapidly. For these RNAs, MAKER uses TBLASTX to align them in protein space.

- Protein sequence generally diverges quite slowly over large evolutionary distances, as a result proteins from even evolutionarily distant organisms can be aligned against raw genomic sequence to try and identify regions of homology. MAKER does this using BLASTX.

Remember now that we are aligning against the repeat-masked genomic sequence. How is this going to affect our alignments? For one thing we won't be able to align against low-complexity regions. Some real proteins contain low-complexity regions and it would be nice to identify those, but if I let anything align to a low-complexity region, then I will get spurious alignments all over the genome. Wouldn't it be nice if there was a way to allow BLAST to extend alignments through low-complexity regions, but only if there is is already alignment somewhere else? You can do this with soft-masking. If you remember soft-masking is using lower case letters to mask sequence without losing the sequence information. BLAST allows you to use soft-masking to keep alignments from seeding in low-complexity regions, but allows you to extend through them. This of course will allow some of the spurious alignments you were trying to avoid, but overall you still end up suppressing the majority of poor alignments while letting through enough real alignments to justify the cost. You can turn this behavior off though if it bothers you by setting softmask=0 in the maker_bopt.ctl file.

Polishing Evidence Alignments

Because of oddities associated with how BLAST statistics work, BLAST alignments are not as informative as they could be. BLAST will align regions any where it can, even if the algorithm aligns regions out of order, with multiple overlapping alignments in the exact same region, or with slight overhangs around splice sites.

To get more informative alignments MAKER uses the program Exonerate to polish BLAST hits. Exonerate realigns each sequences identified by BLAST around splice sites and forces the alignments to occur in order. The result is a high quality alignment that can be used to suggest near exact intron/exon positions. Polished alignments are produced using the est2genome and protein2genome options for Exonerate.

One of the benefits of polishing EST alignments is the ability to identify the strand an EST derives from. Because of amplification steps involved in building an EST library and limitations involved in some high throughput sequencing technologies, you don't necessarily know whether you're really aligning the forward or reverse transcript of an mRNA. However, if you take splice sites into account, you can only align to one strand correctly.

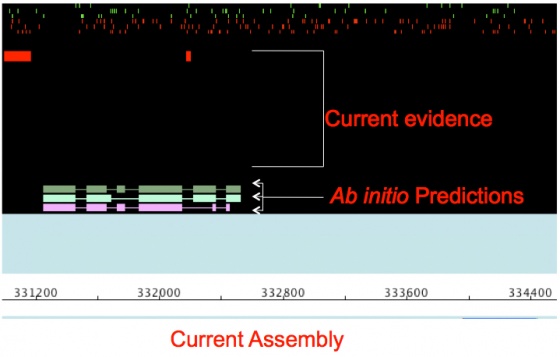

Integrating Evidence to Synthesize Annotations

Once you have ab initio predictions, EST alignments, and protein alignments you can integrate this evidence to produce even better gene predictions. MAKER does this by communicating with the gene prediction programs. MAKER takes all the evidence, generates "hints" to where splice sites and protein coding regions are located, and then passes these "hints" to programs that will accept them.

MAKER produces hint based predictors for:

- SNAP

- Augustus

- FGENESH

- GeneMark (under development)

Selecting and Revising the Final Gene Model

MAKER then takes the entire pool of ab initio and evidence informed gene predictions, updates features such as 5' and 3' UTRs based on EST evidence, tries to determine alternative splice forms where EST data permits, produces quality control metrics for each gene model (this is included in the output), and then MAKER chooses from among all the gene model possibilities the one that best matches the evidence. This is done using a modified sensitivity/specificity distance metric.

MAKER can use evidence from EST alignments to revise gene models to include features such as 5' and 3' UTRs.

Quality Control

Finally MAKER calculates quality control statistics to assist in downstream management and curation of gene models outside of MAKER.

MAKER's Output

If you look in the current working directory, you will see that MAKER has created an output directory called dpp_contig.maker.output. The name of the output directory is based on the input genomic sequence file, which in this case was dpp_contig.fasta.

Now let's see what's inside the output directory.

cd dpp_contig.maker.output ls -1

You should now see a list of directories and files created by MAKER.

dpp_contig_datastore dpp_contig_master_datastore_index.log maker_bopts.log maker_exe.log maker_opts.log mpi_blastdb seen.dbm

- The maker_opts.log, maker_exe.log, and maker_bopts.log files are logs of the control files used for this run of MAKER.

- The mpi_blastdb directory contains FASTA indexes and BLAST database files created from the input EST, protein, and repeat databases.

- The dpp_contig_master_datastore_index.log contains information on both the run status of individual contigs and information on where individual contig data is stored.

- The dpp_contig_datastore directory contains a set of subfolders, each containing the final MAKER output for individual contigs from the genomic fasta file.

Once a MAKER run is finished the most important file to look at is the dpp_contig_master_datastore_index.log to see if there were any failures.

less -S dpp_contig_master_datastore_index.log

If everything proceeded correctly you should see the following:

contig-dpp-500-500 dpp_contig_datastore/05/1F/contig-dpp-500-500/ STARTED contig-dpp-500-500 dpp_contig_datastore/05/1F/contig-dpp-500-500/ FINISHED

There are only entries describing a single contig because there was only one contig in the example file. These lines indicate that the contig contig-dpp-500-500 STARTED and then FINISHED without incident. Other possible entries include:

- FAILED - indicates a failed run on this contig, MAKER will retry these

- RETRY - indicates that MAKER is retrying a contig that failed

- SKIPPED_SMALL - indicates the contig was too short to annotate (minimum contig length is specified in maker_opt.ctl)

- DIED_SKIPPED_PERMANENT - indicates a failed contig that MAKER will not attempt to retry (number of times to retry a contig is specified in maker_opt.ctl)

The entries in the dpp_contig_master_datastore_index.log file also indicate that the output files for this contig are stored in the directory dpp_contig_datastore/contig-dpp-500-500/. Knowing where the output is stored may seem trivial, however, input genome fasta files can contain thousands even hundreds-of-thousands of contigs, and many file-systems have performance problems with large numbers of sub-directories and files within a single directory. Even when the underlying file-system handles things gracefully, access via network file-systems can still be an issue. To deal with this problem, MAKER creates a hierarchy of nested sub-directory layers, starting from a 'base', and places the results for a given contig within these datastore of possibly thousands of nested directories. The master_datastore_index.log file this is essential for identifying where the output for a given contig is stored.

Now let's take a look at what MAKER produced for the contig 'contig-dpp-500-500'.

cd dpp_contig_datastore/05/1F/contig-dpp-500-500/ ls -1

The directory should contain a number of files and a directory.

contig-dpp-500-500.gff contig-dpp-500-500.maker.proteins.fasta contig-dpp-500-500.maker.transcripts.fasta contig-dpp-500-500.maker.trnascan.transcripts.fasta run.log theVoid.contig-dpp-500-500

- The contig-dpp-500-500.gff contains all annotations and evidence alignments in GFF3 format. This is the important file for use with Apollo or GBrowse.

- The contig-dpp-500-500.maker.transcripts.fasta and contig-dpp-500-500.maker.proteins.fasta files contain the transcript and protein sequences for MAKER produced gene annotations.

- The run.log file is a log file. If you change settings and rerun MAKER on the same dataset, or if you are running a job on an entire genome and the system fails, this file lets MAKER know what analyses need to be deleted, rerun, or can be carried over from a previous run. One advantage of this is that rerunning MAKER is extremely fast, and your runs are virtually immune to all system failures.

- The directory theVoid.contig-dpp-500-500 contains raw output files from all the programs MAKER runs (Blast, SNAP, RepeatMasker, etc.). You can usually ignore this directory and its contents.

Viewing MAKER Annotations

Let's take a look at the GFF3 file produced by MAKER.

less contig-dpp-500-500.gff

As you can see, manually viewing the raw GFF3 file produced by MAKER really isn't that meaningful. While you can identify individual features such as genes, mRNAs, and exons, trying to interpret those features in the context of thousands of other genes and thousands of bases of sequence really can't be done by directly looking at the GFF3 file.

For sanity check purposes it would be nice to have a graphical view of what's in the GFF3 file. To do that, GFF3 files can be loaded into programs like Apollo and GBrowse.

Apollo

While genome browsers like Gbrowse and JBrowse are very useful for displaying and distributing our annotations to the broader scientific community, since we've created and maintain these annotations we'll want to be able to manually curate them. [Apollo] is the tool for this job!

Apollo comes in two flavors a desktop application and a web-application. For a quick look at the annotations the Apollo desktop application is about as easy to use as it gets. We could run Apollo on our AWS server to view our annotations on our laptop by setting up X-11 forwarding, but with a roomful of us running GUIS on a remote server over a shared wireless connection is asking for trouble. So let's copy our genome files to our laptop and view them there. If you don't have Apollo installed on your local machine just follow along for a while on the main screen or a neighbor's computer.

scp -i .ssh/summerschool.pem ubuntu@ec2-107-22-1-182.compute-1.amazonaws.com:\ /home/ubuntu/maker/maker_course/example1_dmel/dpp_contig.maker.output/\ dpp_contig_datastore/05/1F/contig-dpp-500-500/contig-dpp-500-500.gff

Your AWS connection string will be different.

Before starting Apollo let's configure it for MAKER output. MAKER comes with a configuration file that will allow Apollo to display MAKER annotations and evidence in nice color (otherwise everything will be the same color of white). Put a copy of this configuration file ~/.apollo directory. If you are on a mac this files goes here /Applications/Apollo.app/Contents/Resources/app/

Now start Apollo and load the contig-dpp-500-500.gff into Apollo and take a look at what MAKER produced. We put the contig-dpp-500-500.gff file in our home directory to make it easy to locate.

You will notice that there are a number of bars representing the gene annotations and the evidence alignments supporting those annotations. Annotations are in the middle light colored panel, and evidence alignments are in the dark panels at the top and bottom. As you have probably realized, this view is much easier to interpret than looking directly at the GFF3 file.

Now click on each piece of evidence and you will see its source in the table at the bottom of the Apollo screen.

Possible Sources Include:

- BLASTN - BLASTN alignment of EST evidence

- BLASTX - BLASTX alignment of protein evidence

- TBLASTX - TBLASTX alignment of EST evidence from closely related organisms

- EST2Genome - Polished EST alignment from Exonerate

- Protein2Genome - Polished protein alignment from Exonerate

- SNAP - SNAP ab inito gene prediction

- GENEMARK - GeneMarkab inito gene prediction

- Augustus - Augustus ab inito gene prediction

- FgenesH - FGENESH ab inito gene prediction

- Repeatmasker - RepeatMasker identified repeat

- RepeatRunner - RepeatRunner identified repeat from the repeat protein database

- tRNAScan - tRNAScan-SE tRNA predictions (coming soon)

- PASA - PASA gene predictions (coming soon)

GAL (genome annotation library)

In addition to visualizing our annotations we also want some basic statistics. We are interested in information such as number of genes, average exon length, average intron length, and fraction of splice sites confirmed by mRNA-seq data can give us insights into the quality of our annotations. These data also give us a way to compare multiple annotations of the same genome. The genome analysis library (GAL) is an object oriented perl library designed to simplify writing code to analyze data in gff3 format. Lets look at a script that takes a MAKER generated gff3 file, and using GAL, returns some basic statistics from our annotation.

nano ~/maker_course/GAL_scripts/Simple_GAL_script.pl

#!/usr/bin/perl

# Use the module in GAL that lets you make the annotation object

use GAL::Annotation;

#-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

#----------------------------------- MAIN ------------------------------------

#-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

my $usage = "\n\n\t

This is to get you started using GAL. This script will return

the total number and average lengths of specified features in

a gff3 file

Simple_GAL_script.pl GFF3.gff FASTA.fa

\n\n";

die($usage) unless $ARGV[1];

my ( $GFF3, $FASTA ) = @ARGV;

# Make an annotation object

my $ANNOTATION = GAL::Annotation->new( $GFF3, $FASTA );

# Make a Features object using the annotation object

my $FEATURES = $ANNOTATION->features;

get_length_and_count($FEATURES);

#-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

#---------------------------------- SUBS -------------------------------------

#-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

sub get_length_and_count{

my $features_obj = shift;

my $mRNA_count =0;

my $mRNA_length =0;

my $exon_count =0;

my $exon_length =0;

my $intron_count =0;

my $intron_length =0;

# Do a search of the feature object and get an iterator object for all of the mRNAs

my $mRNAs = $features_obj->search( { type => 'mRNA' } );

# Get the number of mRNAs

$mRNA_count = $mRNAs->count;

# Go through the mRNAs one at a time

while ( my $mRNA = $mRNAs->next ) {

# Get the length of the mRNA

$mRNA_length += $mRNA->length;

# Get an iterator object for the exons

my $exons = $mRNA->exons;

# Get the number of exons in the mRNA

$exon_count += $exons->count;

# Do a search of the mRNA object and get an iterator object for all of the exons

while (my $exon = $exons->next){

$exon_length += $exon->length;

}

# Even though introns do not technically exist in the gff3 file, GAL will infer them

my $introns = $mRNA->introns;

$intron_count += $introns->count;

while (my $intron = $introns->next){

$intron_length += $intron->length;

}

}

# Print out what you found

print "\n\nfeature type\tcount\taverage_length\n";

print "mRNA\t$mRNA_count\t". int($mRNA_length/$mRNA_count)."\n";

print "exon\t$exon_count\t". int($exon_length/$exon_count)."\n";

print "intron\t$intron_count\t". int($intron_length/$intron_count)."\n";

}

Now lets see what happens when we run it on our data

~/maker_course/GAL_scripts/Simple_GAL_script.pl \ contig-dpp-500-500.gff \ ~/applications/maker/data/dpp_contig.fasta

INFO : fasta_database_loading_indexing : Loading (and possibly indexing) /home/ubuntu/applications/maker/data/dpp_contig.fasta WARN : resetting_attribute_values : GAL::Base is about to reset the value of fasta on behalf of a GAL::Annotation object. This may be a bad idea. INFO : fasta_database_loading_indexing : Loading (and possibly indexing) /home/ubuntu/applications/maker/data/dpp_contig.fasta INFO : loading_database : contig-dpp-500-500.gff INFO : finished_loading_database : contig-dpp-500-500.gff INFO : indexing_database : contig-dpp-500-500.sqlite INFO : indexing_feature_id : contig-dpp-500-500.sqlite INFO : indexing_locus : contig-dpp-500-500.sqlite INFO : indexing_feature_type : contig-dpp-500-500.sqlite INFO : indexing_feature_attributes : contig-dpp-500-500.sqlite INFO : indexing_relationships : contig-dpp-500-500.sqlite INFO : analyzing_database : contig-dpp-500-500.sqlite INFO : finished_indexing_database : contig-dpp-500-500.sqlite feature type count average_length mRNA 3 3777 exon 9 1259 intron 6 2117

In addition to our expected output GAL did a couple of other things that you should be aware of. Namely, GAL created an sqlite database for us out of the gff3 file, and indexed the fasta file. We can see them here.

ls -1 contig-dpp-500-500.gff contig-dpp-500-500.maker.proteins.fasta contig-dpp-500-500.maker.transcripts.fasta contig-dpp-500-500.sqlite <- This is the database run.log

and here

ls -1 ~/applications/maker/data/dpp* /home/ubuntu/applications/maker/data/dpp_contig.fasta /home/ubuntu/applications/maker/data/dpp_contig.fasta.index <- This is the fasta index /home/ubuntu/applications/maker/data/dpp_est.fasta /home/ubuntu/applications/maker/data/dpp_protein.fasta

Saving these files allows GAL scripts to run much faster in subsequent runs. That being said, the GAL library was written under the assumption that user time is more valuable than computation time. The intuitive object oriented nature of GAL can dramatically decrease development time, but there is a cost in run time. If you are iterating over thousands of genes and descending the sequence ontology to capture exons, infer introns, and translate CDSs into proteins; you are going to want to write the script, start it running, and go to lunch.

Advanced MAKER Configuration, Re-annotation Options, and Improving Annotation Quality

The remainder of this page addresses issues that can be encountered during the annotation process. I then describe how MAKER can be used to resolve each issue.

Configuration Files in Detail

Let's take a closer look at the configuration options in the maker_opt.ctl file.

cd /home/ubuntu/maker_course/example1_dmel nano maker_opts.ctl

Genome Options (Required)

genome=dpp_contig.fasta #genome sequence (fasta file or fasta embeded in GFF3 file) organism_type=eukaryotic #eukaryotic or prokaryotic. Default is eukaryotic

Re-annotation Using MAKER Derived GFF3

maker_gff= #MAKER derived GFF3 file est_pass=0 #use ESTs in maker_gff: 1 = yes, 0 = no altest_pass=0 #use alternate organism ESTs in maker_gff: 1 = yes, 0 = no protein_pass=0 #use protein alignments in maker_gff: 1 = yes, 0 = no rm_pass=0 #use repeats in maker_gff: 1 = yes, 0 = no model_pass=0 #use gene models in maker_gff: 1 = yes, 0 = no pred_pass=0 #use ab-initio predictions in maker_gff: 1 = yes, 0 = no other_pass=0 #passthrough anyything else in maker_gff: 1 = yes, 0 = no

RNA (EST) Evidence

est=dpp_transcripts.fasta #set of ESTs or assembled mRNA-seq in fasta format altest= #EST/cDNA sequence file in fasta format from an alternate organism est_gff= #aligned ESTs or mRNA-seq from an external GFF3 file altest_gff= #aligned ESTs from a closly relate species in GFF3 format

Protein Homology Evidence

protein=dpp_proteins.fasta #protein sequence file in fasta format (i.e. from mutiple oransisms) protein_gff= #aligned protein homology evidence from an external GFF3 file

Repeat Masking

model_org=all #select a model organism for RepBase masking in RepeatMasker rmlib= #provide an organism specific repeat library in fasta format for RepeatMasker repeat_protein=/usr/local/maker/data/te_proteins.fasta #provide # [cont'd] a fasta file of transposable element proteins for RepeatRunner rm_gff= #pre-identified repeat elements from an external GFF3 file prok_rm=0 #forces MAKER to repeatmask prokaryotes # [cont'd] (no reason to change this), 1 = yes, 0 = no softmask=1 #use soft-masking rather than hard-masking in BLAST # [cont'd] (i.e. seg and dust filtering)

Gene Prediction

snaphmm= #SNAP HMM file gmhmm= #GeneMark HMM file augustus_species= #Augustus gene prediction species model fgenesh_par_file= #FGENESH parameter file pred_gff= #ab-initio predictions from an external GFF3 file model_gff= #annotated gene models from an external GFF3 file (annotation pass-through) est2genome=1 #infer gene predictions directly from ESTs, 1 = yes, 0 = no protein2genome=0 #infer predictions from protein homology, 1 = yes, 0 = no trna=0 #find tRNAs with tRNAscan, 1 = yes, 0 = no snoscan_rrna= #rRNA file to have Snoscan find snoRNAs unmask=0 #also run ab-initio prediction programs on unmasked sequence, 1 = yes, 0 = no

Other Annotation Feature Types

other_gff= #extra features to pass-through to final MAKER generated GFF3 file

External Application Behavior Options

alt_peptide=C #amino acid used to replace non-standard amino acids in BLAST databases cpus=1 #max number of cpus to use in BLAST and RepeatMasker (not for MPI, leave 1 when using MPI)

MAKER Behavior Options

max_dna_len=100000 #length for dividing up contigs into chunks (increases/decreases memory usage) min_contig=1 #skip genome contigs below this length (under 10kb are often useless) pred_flank=200 #flank for extending evidence clusters sent to gene predictors pred_stats=0 #report AED and QI statistics for all predictions as well as models AED_threshold=1 #Maximum Annotation Edit Distance allowed (bound by 0 and 1) min_protein=0 #require at least this many amino acids in predicted proteins alt_splice=0 #Take extra steps to try and find alternative splicing, 1 = yes, 0 = no always_complete=0 #extra steps to force start and stop codons, 1 = yes, 0 = no map_forward=0 #map names and attributes forward from old GFF3 genes, 1 = yes, 0 = no keep_preds=0 #Concordance threshold to add unsupported gene prediction (bound by 0 and 1) split_hit=10000 #length for the splitting of hits (expected max intron size for evidence alignments) single_exon=0 #consider single exon EST evidence when generating annotations, 1 = yes, 0 = no single_length=250 #min length required for single exon ESTs if 'single_exon is enabled' correct_est_fusion=0 #limits use of ESTs in annotation to avoid fusion genes tries=2 #number of times to try a contig if there is a failure for some reason clean_try=0 #remove all data from previous run before retrying, 1 = yes, 0 = no clean_up=0 #removes theVoid directory with individual analysis files, 1 = yes, 0 = no TMP= #specify a directory other than the system default temporary directory for temporary files

Training ab initio Gene Predictors

If you are involved in a genome project for an emerging model organism, you should already have an EST database, or more likely now mRANA-Seq data, which would have been generated as part of the original sequencing project. A protein database can be collected from closely related organism genome databases or by using the UniProt/SwissProt protein database or the NCBI NR protein database. However a trained ab initio gene predictor is a much more difficult thing to generate. Gene predictors require existing gene models on which to base prediction parameters. However, with emerging model organisms you are not likely to have any pre-existing gene models. So how then are you supposed to train your gene prediction programs?

MAKER gives the user the option to produce gene annotations directly from the EST evidence. You can then use these imperfect gene models to train gene predictor program. Once you have re-run MAKER with the newly trained gene predictor, you can use the second set of gene annotations to train the gene predictors yet again. This boot-strap process allows you to iteratively improve the performance of ab initio gene predictors.

I've created an example file set so you can learn to train the gene predictor SNAP using this procedure.

First let's move to the example directory.

cd /home/ubuntu/maker_course/example2_pyu ls -1

This directory looks just like the one from example1

finished.maker.output opts.txt

We need to build maker configuration files and populate the appropriate values.

maker -CTL cp opts.txt maker_opts.ctl or cp /path/to/maker/data/pyu* . and edit nano maker_opts.ctl genome=pyu_contig.fasta est=pyu_est.fasta protein=pyu_protein.fasta est2genome=1

MAKER is now configured to generate annotations from the EST data, so start the program (this will take a minute or 20 to run).

maker

Once finished load the file pyu_contig.maker.output/pyu-contig_datastore/09/14/scf1117875582023/scf1117875582023.gff into Apollo. You will see that there are far more regions with evidence alignments than there are gene annotations. This is because there are so few spliced ESTs that are capable of generating gene models.

Now exit Apollo. We now need to convert the GFF3 gene models to ZFF format. This is the format SNAP requires for training. To do this wee need to collect all GFF3 files into a single directory.

mkdir snap cp pyu-contig.maker.output/pyu-contig_datastore/09/14/scf1117875582023/scf1117875582023.gff snap/ cd snap maker2zff scf1117875582023.gff ls -1

There should now be two new files. The first is the ZFF format file and the second is a FASTA file the coordinates can be referenced against. These will be used to train SNAP.

genome.ann genome.dna

The basic steps for training SNAP are first to filter the input gene models, then capture genomic sequence immediately surrounding each model locus, and finally uses those captured segments to produce the HMM. You can explore the internal SNAP documentation for more details if you wish.

fathom -categorize 1000 genome.ann genome.dna fathom -export 1000 -plus uni.ann uni.dna forge export.ann export.dna hmm-assembler.pl pyu . > pyu.hmm cd ..

The final training parameters file is pyu.hmm. We do not expect SNAP to perform that well with this training file because it is based on incomplete gene models; however, this file is a good starting point for further training.

We need to run MAKER again with the new HMM file we just built for SNAP.

nano maker_opts.ctl

And set:

snaphmm=snap/pyu.hmm est2genome=0

And run

maker

Now let's look at the output in Apollo. When you examine the annotations you should notice that final MAKER gene models displayed in light blue, are more abundant now and are in relatively good agreement with the evidence alignments. However the SNAP ab initio gene predictions in the evidence tier do not yet match the evidence that well. This is because SNAP predictions are based solely on the mathematic descriptions in the HMM; whereas, MAKER models also use evidence alignments to help further inform gene models. This demonstrates why you get better performance by running ab initio gene predictors like SNAP inside of MAKER rather than producing gene models by themselves for emerging model organism genomes. The fact that the MAKER models are in better agreement with the evidence than the current SNAP models also means I can use the MAKER models to retrain SNAP in a bootstrap fashion, thereby improving SNAP's performance and consequentially MAKER's performance.

Alternatively we can run our GAL script to get a quick look.

~/maker_course/GAL_scripts/Simple_GAL_script.pl snap/scf1117875582023.gff ~/applications/maker/data/pyu-contig.fasta feature type count average_length mRNA 164 444 exon 479 152 intron 315 90 ~/maker_course/GAL_scripts/Simple_GAL_script.pl \ pyu-contig.maker.output/pyu-contig_datastore/09/14/scf1117875582023/scf1117875582023.gff \ ~/applications/maker/data/pyu-contig.fasta feature type count average_length mRNA 367 1622 exon 1574 378 intron 1207 110

Close Apollo, retrain SNAP, and run MAKER again.

mkdir snap2 cp pyu-contig.maker.output/pyu-contig_datastore/09/14/scf1117875582023/scf1117875582023.gff snap2/ cd snap2 maker2zff scf1117875582023.gff fathom -categorize 1000 genome.ann genome.dna fathom -export 1000 -plus uni.ann uni.dna forge export.ann export.dna hmm-assembler.pl pyu . > pyu2.hmm cd .. nano maker_opts.ctl

Change configuration file.

snaphmm=snap2/pyu2.hmm

Run maker.

maker

Let's examine the GFF3 file one last time in Apollo. As you can see there, there is now a marked degree of improvement in both the MAKER and SNAP gene models, and both models are in more agreement with each other.

Or use the GAL script again

~/maker_course/GAL_scripts/Simple_GAL_script.pl \ pyu-contig.maker.output/pyu-contig_datastore/09/14/scf1117875582023/scf1117875582023.gff \ ~/applications/maker/data/pyu-contig.fasta feature type count average_length mRNA 396 1630 exon 1647 391 intron 1251 108

Improving Annotation Quality with MAKER's AED score

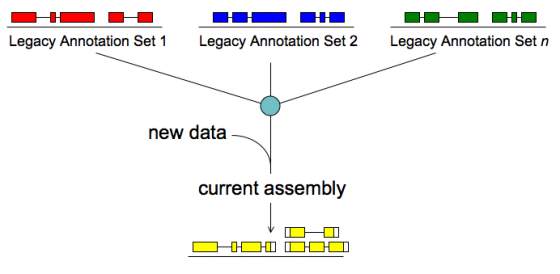

Merge/Resolve Legacy Annotations

Legacy annotations

- Many are no longer maintained by original creators

- In some cases more than one group has annotated the same genome, using very different procedures, even different assemblies

- Many investigators have their own genome-scale data and would like a private set of annotations that reflect these data

- There will be a need to revise, merge, evaluate, and verify legacy annotation sets in light of RNA-seq and other data

MAKER will:

- Identify legacy annotation most consistent with new data

- Automatically revise it in light of new data

- If no existing annotation, create new one

MPI Support

MAKER optionally supports Message Passing Interface (MPI), a parallel computation communication protocol primarily used on computer clusters. This allows MAKER jobs to be broken up across multiple nodes/processors for increased performance and scalability.

To use this feature, you must have MPICH2 installed with the the --enable-sharedlibs flag set during installation (See MPICH2 Installer's Guide). Or openmpi and allow shared libraries by adding a line like this to your profile --export LD_PRELOAD=/home/ubuntu/applications/maker/exe/openmpi/lib/libmpi.so:$LD_PRELOAD I have installed this for you. So let's set up MPI_MAKER and run the example file that comes with MAKER.

cd /usr/local/maker/src perl Build.PL

Say Yes that we want to build for MPI support

./Build install

Set values in maker configuration files.

genome=dpp_contig.fasta est=dpp_est.fasta protein=dpp_protein.fasta snap=$PATH_TO_SNAP/HMM/fly

We need to set up a few more things for MPI to work. Type mpd to see a list of instructions.

mpd

You should see the following.

configuration file /home/ubuntu/.mpd.conf not found A file named .mpd.conf file must be present in the user's home directory (/etc/mpd.conf if root) with read and write access only for the user, and must contain at least a line with: MPD_SECRETWORD=<secretword> One way to safely create this file is to do the following: cd $HOME touch .mpd.conf chmod 600 .mpd.conf and then use an editor to insert a line like MPD_SECRETWORD=mr45-j9z into the file. (Of course use some other secret word than mr45-j9z.)

Follow the instructions to set this file up, and start the mpi environment with mpdboot. Then run maker through the MPI manager mpiexec.

mpdboot mpiexec -n 2 maker </dev/null

mpiexec is a wrapper that handles the MPI environment. The -n 2 flag tells mpiexec to use 2 cpus/nodes when running maker. For a large cluster, this could be set to something like 100. You should now know how to start a MAKER job via MPI.

MAKER Accessory Scripts

MAKER comes with a number of accessory scripts that assist in manipulations of the MAKER input and output files.

Scripts:

- cegma2zff' - This script converts the output of a GFF file from CEGMA into ZFF format for use in SNAP training. Output files are always genome.ann and genome.dna

cegma2zff <cegma_gff> <genome_fasta>

- chado2gff3 - This script takes default CHADO database content and produces GFF3 files for each contig/chromosome.

chado2gff3 [OPTION] <database_name>

- compare - This script compares the contents of a GFF3 file to a CHADO database to look for merged, split and missing genes.

compare [OPTION] <database_name> <gff3_file>

- cufflinks2gff3 - This script converts the cufflinks output transcripts.gtf file into GFF3 format for use in MAKER via GFF3 passthrough. By default strandless features which correspond to single exon cufflinks models will be ignored. This is because these features can correspond to repetative elements and pseudogenes. Output is to STDOUT so you will need to redirect to a file.

cufflinks2gff3 <transcripts1.gtf> <transcripts2.gtf> ...

- evaluator - Evaluate the the quality of an annotation set.

mpi_evaluator [options] <eval_opts> <eval_bopts> <eval_exe>

- fasta_merge - Collects all of MAKER's fasta file output for each contig and merges them to make genome level fastas

fasta_merge -d <datastore_index> -o <outfile>

- fasta_tool - The script can search, reformat, and manipulate a fasta file in a variety of ways.

- fix_fasta - Deprecated, use fasta_tool

- genemark_gtf2gff3 - This converts genemark's GTF output into GFF3 format. The script prints to STDOUT. Use the '>' character to redirect output into a file.

genemark_gtf2gff3 <filename>

- gff3_merge - Collects all of MAKER's GFF3 file output for each contig and merges them to make a single genome level GFF3

gff3_merge -d <datastore_index> -o <outfile>

- gff3_preds2models - Deprecated pass the predictions to MAKER in the maker_opts.ctl in gff3 format here pred_gff= and set keep_preds=1

- maker2eval_gtf - This script converts MAKER GFF3 files into GTF formated files for the program EVAL (an annotation sensitivity/specificity evaluating program). The script will only extract features explicitly declared in the GFF3 file, and will skip implicit features (i.e. UTR, start codons, and stop codons). To extract implicit features to the GTF file, you will first need to expicitly declare them in the GFF3 file. This can be done by calling the script add_utr_to_gff3 to add formal declaration lines to the GFF3 file.

maker2eval_gtf <maker_gff3_file>

- iprscan2gff3 - Takes InerproScan (iprscan) output and generates GFF3 features representing domains. Interesting tier for GBrowse.

iprscan2gff3 <iprscan_file> <gff3_fasta>

- iprscan_wrap - A wrapper that will run iprscan

- ipr_update_gff - Takes InterproScan (iptrscan) output and maps domain IDs and GO terms to the Dbxref and Ontology_term attributes in the GFF3 file.

ipr_update_gff <gff3_file> <iprscan_file>

- maker2chado - This script takes MAKER produced GFF3 files and dumps them into a Chado database. You must set the database up first according to CHADO installation instructions. CHADO provides its own methods for loading GFF3, but this script makes it easier for MAKER specific data. You can either provide the datastore index file produced by MAKER to the script or add the GFF3 files as command line arguments.

maker2chado [OPTION] <database_name> <gff3file1> <gff3file2> ...

- maker2jbrowse - This script will produce a JBrowse data set from MAKER gff3 files.

maker2chado [OPTION] <database_name> <gff3file1> <gff3file2> ...

- maker2zff - Pulls out MAKER gene models from the MAKER GFF3 output and convert them into ZFF format for SNAP training.

maker2zff <gff3_file>

- maker_functional

- maker_functional_fasta - Maps putative functions identified from BLASTP against UniProt/SwissProt to the MAKER produced tarnscript and protein fasta files.

maker_functional_fasta <uniprot_fasta> <blast_output> <fasta1> <fasta2> <fasta3> ...

- maker_functional_gff - Maps putative functions identified from BLASTP against UniProt/SwissProt to the MAKER produced GFF3 files in the Note attribute.

maker_functional_gff <uniprot_fasta> <blast_output> <gff3_1>

- maker_map_ids - Build shorter IDs/Names for MAKER genes and transcripts following the NCBI suggested naming format.

maker_map_ids --prefix PYU1_ --justify 6 genome.all.gff > genome.all.id.map

- map2assembly - Maps old gene models to a new assembly where possible.

map2assembly <genome.fasta> <transcripts.fasta>

- map_data_ids - This script takes a id map file and changes the name of the ID in a data file. The map file is a two column tab delimited file with two columns: old_name and new_name. The data file is assumed to be tab delimited by default, but this can be altered with the delimit option. The ID in the data file can be in any column and is specified by the col option which defaults to the first column.

map_data_ids genome.all.id.map data.txt

- map_fasta_ids - Maps short IDs/Names to MAKER fasta files.

map_fasta_ids <map_file> <fasta_file>

- map_gff_ids - Maps short IDs/Names to MAKER GFF3 files, old IDs/Names are mapped to to the Alias attribute.

map_gff_ids <map_file> <gff3_file>

- tophat2gff3 - This script converts the juctions file producted by TopHat into GFF3 format for use with MAKER.

tophat2gff3 <junctions.bed>